When hiking across Spitsbergen’s blooming tundra at the peak of spring (mid-June) (Photo 1), we sink in bog-like mosses and lichens, passing Arctic mushrooms, which – despite their diminutive size – still tower over the archipelago’s miniature trees. It is, therefore, only natural that the question posed in the title raises eyebrows. A jungle? You mean, here??

Photo 1. The tundra of Spitsbergen in spring. Photo credit: J. Giżejewski

It is clearly not the present-day vegetation of Spitsbergen that inspired the question, so what did?

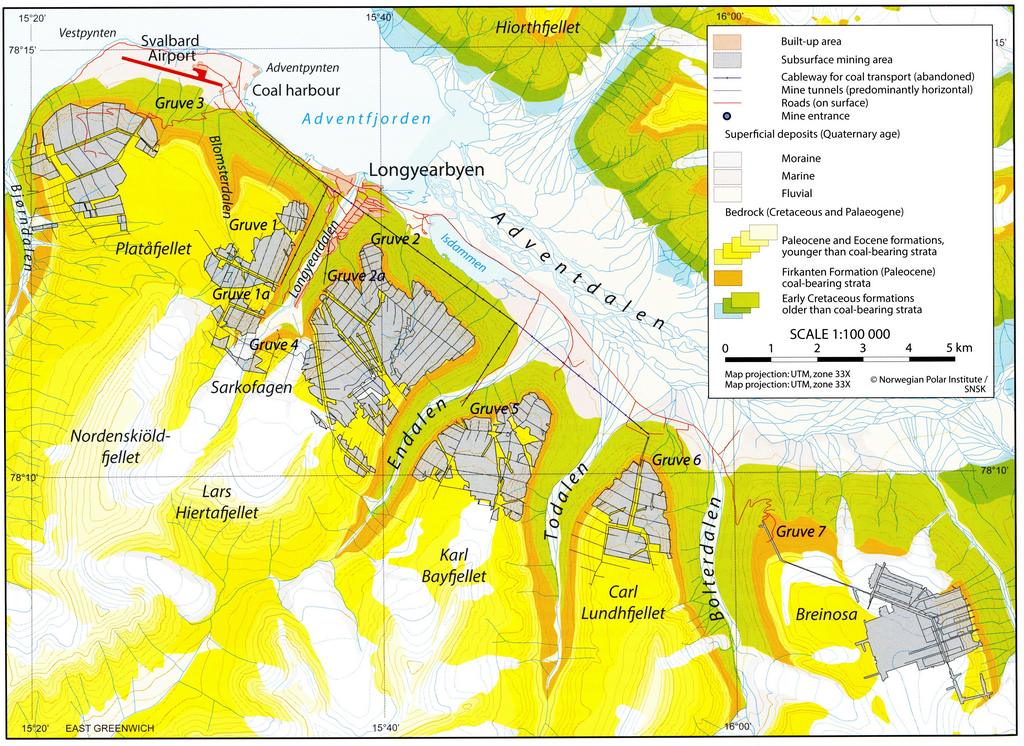

If we follow the only paved road leading out of Longyearbyen, the capital of Svalbard, and enter Adventdalen, we will now and again pass hefty closed trucks (whose bodies were, by the way, designed and produced in Poland). They head to the Longyearbyen Heat and Power Plant and then back into the valley, where they take the turn for “Gruve 7” and continue towards a cluster of buildings perched high on the valley slope. “Gruve 7” is the last active coal mine in the area (expected to shut down in 2023) and the source of fuel for the plant. It is, in other words, thanks to the mine that the people of Longyearbyen may enjoy electricity and heating.

Photo 2. The buildings of Mine 7. Photo credit: M. Schütz, polarjournal.ch/en/2021/10/01

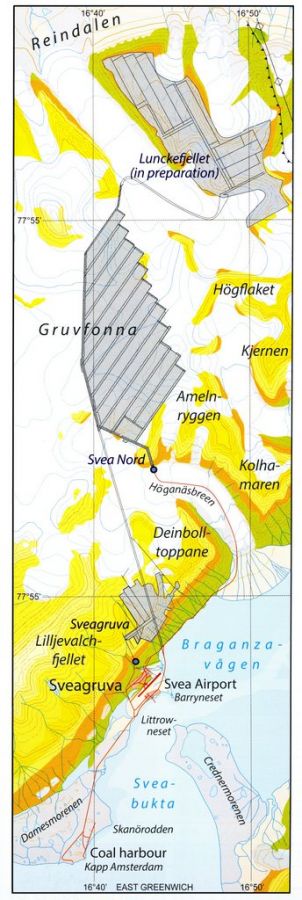

It takes no more than a glance to notice that mountain slopes surrounding the town of Longyearbyen are dotted with entrances to mine drifts, thick steel cables distorted by landslides (Photo 3) and rows of wooden structures resembling electricity pylons (Photo 4). These are the carefully preserved remains of old cableways, which used to carry the coal extracted in the many mines scattered throughout the valley to a warehouse located near the port, where it was loaded onto ships. In its heyday, the mines of Longyearbyen produced 4 million tonnes of coal a year. Now the number is down to a hundred thousand. Norway has no coal deposits other than those found in Spitsbergen and the Bear Island, and – apart from the mines near Longyearbyen – Norwegians operated a mine in Svea, in the most westerly branch of Van Mijenfjorden (Photo 6). In 2014, there was still talk of developing and expanding the mine, but three years later a decision was made to close it down and clear the settlement. The process is to be completed by 2023.

Photo 3. Tracks of a mine railway deformed in a landslide. Photo credit: J. Giżejewski

The conditions of coal extraction from deposits located in Isfjorden are far from easy. Even though coal seams are almost horizontal, they are only about 1,5 m thick, as a result of which the galleries and extraction zones are low and often require work to be done on hands and knees or lying down, with very limited options for mechanized extraction. Tourists may experience these conditions first-hand by visiting a model of a mine on display in Svalbard Museum in Longyearbyen.

Photo 4. Cableway used for coal transport. Source: W.K. Dallman (ed.) 2015. Geoscience Atlas of Svalbard, Norwegian Polar Institute Report Series 148, Tromsø (WKD)

Photo 5. Adventdalen; coal mines in the vicinity of Longyearbyen, location and fields of exploitation. Source: WKD

While at the museum, it is also possible to see carbonized remains of plants, often arborescent (which is to say, tree-like), preserved in coal seams. And this provides an answer, however imprecise, to our title question. Yes, there used to be forests in Spitsbergen, which – back in the Late Cretaceous and Tertiary periods – occupied the edge of Eurasia, separated from Greenland by the narrows of the North Atlantic (today the Fram Strait). The Eurasian continent comprised areas of densely forested high ground separated by boggy depressions, which gradually filled with plant material carried down from the forests and covered with sand and gravel transported by large braided rivers. The lush, heat-loving flora could flourish because the Earth of the day was generally a warmer place. Spitsbergen did not lie much further south than it does nowadays, but in the Cretaceous and the Lower Tertiary its mean annual temperature was significantly higher than the -7°C of today.

Photo 6. Svea; location and fields of exploitation. Source: WKD

Between 1918 and 1962, coal deposits of the same age as those found around Longyearbyen were also exploited further north, in Ny-Ålesund, but the mine was shut down after a series of methane explosions, which killed several dozen miners.

In the area of Isfjorden, coal was – and still is – extracted not only by the Norwegians, but also by the Russians, who in the years 1913–1962 operated in Grumant and Colesbukta (now abandoned) and are still present in the largest mining town of Barentsburg. Between 2002 and 2004, the annual coal production in Barentsburg amounted to 300 000 tonnes. Now it is much less than that and the town is gradually shifting its focus to tourism and (having its own research centre) to science.

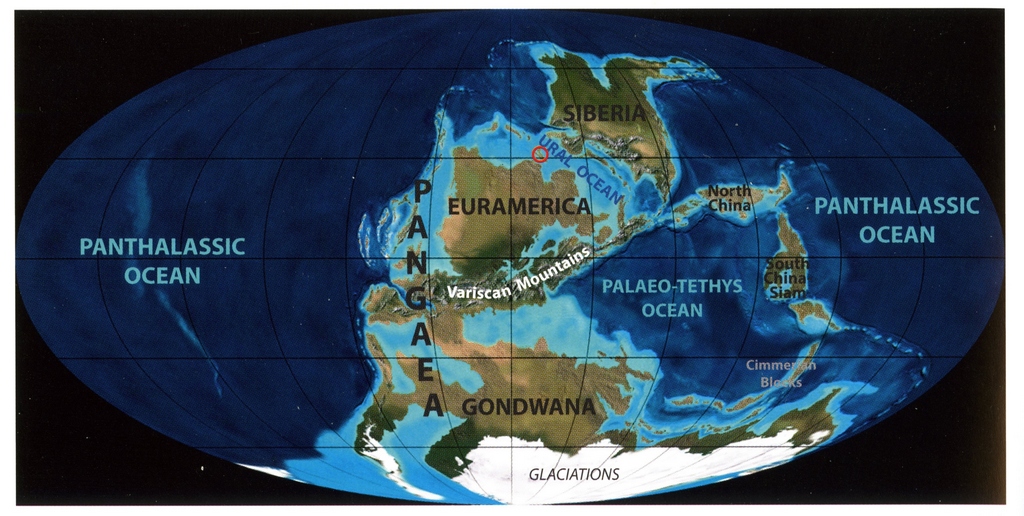

The key area in our search for Spitsbergen’s jungle is the coal mining settlement of Pyramiden, located deep inside Isfjorden, at the shore of Billefjorden (Photo 7). Found there is the only mine in Spitsbergen to have exploited Carboniferous coal deposits. In the Carboniferous period, what is now Spitsbergen lay close to the equator, at the northern edge of Euramerica (Figure 8), within the zone of the humid tropical climate. Plant fossils found in the coal deposits of Pyramiden prove beyond any doubt that, unbelievable though it may seem, back in the day the area was indeed covered with swampy forests of arborescent horsetails, lycophytes and ferns. In other words, it’s in the coal deposits of Pyramiden that we finally find a proper jungle.

Photo 7. The mining settlement of Pyramiden. Source: https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyramiden

Figure 8. W.K. Dallman (ed.) 2015. Geoscience Atlas of Svalbard, Norwegian Polar Institute Report Series 148, Tromsø (WKD)

The coal found in Pyramiden has a very high carbon content, as much of it is anthracite. Anthracite was used as high-energy fuel for enormous, steam icebreakers, built by the Russian since the end of the 19th century. Yermak, or the world’s first polar icebreaker, was launched in 1898.

The coal mine in Pyramiden was built by the Swedish in 1911 and sold to Russia in 1927. It was active until 1 October 1998, when all mining activity was suddenly stopped and the settlement swiftly evacuated. Nowadays, attempts are made to turn it into an open-air museum and a tourist attractions. There seem to be no plans, however, to open the mine itself to the public.

And going back to our initial question, it’s all a matter of scale. If we expand our search to span the last 400 million years, we will readily find a lush tropical jungle covering what is now a treeless Arctic archipelago with the annual mean temperature of -7°C.

Text: Jerzy Giżejewski

English translation: Barbara Jóźwiak