Trapper cabins have been an integral part of Svalbard’s scenery for more than two hundred years. Over time, they’ve changed hands and character, undergone alterations and renovations, while those which were already beyond repair became a source of material for the construction of new cabins, thus going through partial reincarnation.

And although trappers had at their disposal some 60 000 km2 of no man’s land, from generation to generation they often held on to the same sites and the same building solutions. Individual preferences regarding structural and interior design were typically forgotten in the face of material limitations and practical considerations. As a result, trapper cabins scattered across Svalbard have quite a lot in common.

First of all, regardless of their location, they were all made of wood. Even though the archipelago has no trees in the classical sense of the word (“woody plants” that grow there are only about 10 cm tall), it isn’t at all short of timber. This is because found on local beaches are heavy wooden logs that make it to Svalbard from Siberia. For decades, trees felled in Siberian taiga have been floated down rivers, a process not nearly as easy as it might appear. Tree trunks transported in such a manner regularly get out of control and, instead of reaching their destination, end up in the Arctic Ocean. Once there, they’re carried off by sea currents towards the coast of Svalbard, where they often bundle together into peculiar building depots. It happened every so often that trapping expeditions brought timber for cabin construction from the mainland, but most trappers relied heavily on local resources, that is driftwood and elements recycled from ruined buildings.

Stray Siberian tree trunks on the coast of Svalbard

© Barbara Jóźwiak (from the archive of Fundacja forScience)

A driftwood back-up cabin in Breineset, commonly referred to as Hilton (year built: 1970)

© Adam Nawrot (from the archive of Fundacja forScience)

Since the mid-1970s, when changes to the local law put an end to trapping activity in Svalbard, driftwood has mainly been used to protect existing cabins against the more inquisitive polar bears. Massive wooden logs are propped against doors and windows in order to block them and thus make unsolicited visits less likely to occur during prolonged absence of human residents. Besides, driftwood is used to build more permanent structures, whose aim is to strengthen and shield the main entrance. A typical bear won’t fit through the gap between the trunks or manage to squeeze in from the side. One may hope, therefore, that – having carefully sniffed at every available nook and cranny – the bear will lose interest and walk away. Just in case it got inside nonetheless, there’s another challenge waiting for it right behind the door: a minuscule anteroom, whose diminutive size should discourage the bear from further explorations. And although the anterooms are an original element of many old cabins (those large enough to hold one), archive photos suggest that the remaining protective measures were not at all popular during the trapping era. Trappers seem to have favoured more straightforward methods, which let them eliminate not only the danger itself, but also the bear that posed it.

Driftwood logs at the service of Hyttevika (year built: 1907)

© UiT Norges arktiske universitet (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Main entrance to the trapper cabin in Palffyodden (year built: 1966)

© Adam Nawrot (from the archive of Fundacja forScience)

Windows constitute another characteristic feature of local design. They’re small, rare (with most cabins having just one) and usually equipped with more or less makeshift bars and shutters, kept in place in most ingenious ways. Make sure to examine them closely before you open them up, not just to fully appreciate their creators’ inventiveness, but – much more importantly – to be able to lock them up properly afterwards. In Svalbard, it only takes a tiny crack for snowdrifts to form inside a cabin during a blizzard, and snowdrifts mean damp, which seldom does the cabins any good.

The last essential element of every decent trapper cabin is a stove, usually of the pot-bellied kind, which serves as a heater, cooker and dryer. Despite its annoying habit of turning the cabin into a smoking chamber, without it even the Arctic summer would be difficult to endure. Using a stove, however, involves some difficulties and potential dangers. The most obvious of them is the risk of fire and the prospect of finding oneself, quite literally, out in the cold. Besides, a stove needs a chimney, which in turn requires a hole to be cut in the roof or a wall. A hole of the sort may be tricky to seal, which brings us back to the topic of snowdrifts and damp.

Snowdrifts and pervasive damp are a curse of many old cabins in Svalbard

© Joanna Nawrot (from the archive of Fundacja forScience)

When it comes to building trends prevalent among Svalbard’s trappers, climate was clearly as much of a driving factor as the presence (and inherent inquisitiveness) of polar bears. In order to make the cabins more stable and watertight, and – by the same token – better able to withstand fierce wind, rain and snow, their occupants sometimes covered them from top to bottom with tar paper. The solution was relatively cheap, easy to implement and highly effective, but only as long as the cabins were in use. Once the trappers had left, things took a turn for the worse. Despite additional protection in the form of wooden planks nailed on top of it, much of the tar paper sooner or later succumbed to the wind. As a result, neat protective layers that covered many cabins in the second half of the 20th century are now no more than tattered shreds clinging desperately to the walls. Left to their own fate, former trappers’ bases gradually disintegrate, until all that remains are piles of wood, adorned here and there with pieces of broken equipment.

Remains of a trapper cabin in Raksodden (year built: 1919)

© Adam Nawrot (from the archive of Fundacja forScience)

It's worth remembering, however, that the fate of Svalbard’s cabins depends not only on the mercy of polar bears and Arctic weather, but also on local legislation. According to Lov om miljøvern på Svalbard (or Svalbard Environmental Protection Act), all cabins built by 1 January 1946 constitute Svalbard’s cultural heritage and are therefore protected. Does this have any practical consequences? Absolutely, especially if we don’t want to fall out of favour with local authorities. With the exception of emergency situations, elements of cultural heritage may only be used with the permission of the Governor of Svalbard. On top of that, anyone using them must follow a long (though rather sensible) list of dos and don’ts, which apply not only to the monuments themselves, but also to 100-metre-wide safety zones surrounding each of them.

The problem is that correct identification of Svalbard’s cultural heritage is anything but easy. The protection they enjoy may (or may not) go hand in hand with professional maintenance. This means that cabins from the early 1900s are often doing much better than those built half a century later.

Due to regular repairs, the 100-year-old cabin in Wilczekodden looks as good as new (year built: 1919)

© Adam Nawrot (from the archive of Fundacja forScience)

What’s more, restrictions regarding cultural monuments apply regardless of their condition. As a result, piles of wood left after collapsed buildings, which – due to their age – qualified as cultural heritage, are thought of as more valuable than many cabins which are still perfectly functional.

All in all, before you head to Svalbard for a taste of trapper’s life, you should no doubt read up on the topic and complete all formalities. And then, when you finally reach one of the cabins formerly used by local trappers, remember about the cabin savoir-vivre, whose fundamental rules are as follows:

- Clean and tidy the cabin before you leave (even if the mess wasn’t yours).

- If you’ve used the stove, remove the ash, leave the stove door open and put the chimney cap back on. This way you’ll help to protect the stove from corrosion and prolong its life span.

- Dispose of the ash at a proper distance from the cabin, especially if it’s still hot. Svalbard is famous for strong winds and old timber burns remarkably well.

- Put the matches in a watertight container and restore the supply of firewood. In emergency situations, being able to quickly get a fire going might save somebody’s life.

- Do not leave rubbish or food in the cabin. They are both magnets for polar bears, which – tempted by an unusual scent – are capable of causing considerable damage.

- Carefully close and secure windows and doors, as the snow blown in through the cracks and frozen solid may block the entrance, turning the cabin into an impenetrable fortress.

Why are the above rules so crucial to obey? Because the Arctic does not forgive mistakes and with each ruined cabin we lose, once and for all, an emergency shelter, a chunk of fascinating history and, almost as importantly, an opportunity to become part of that history by adding to it a couple extra paragraphs of our own.

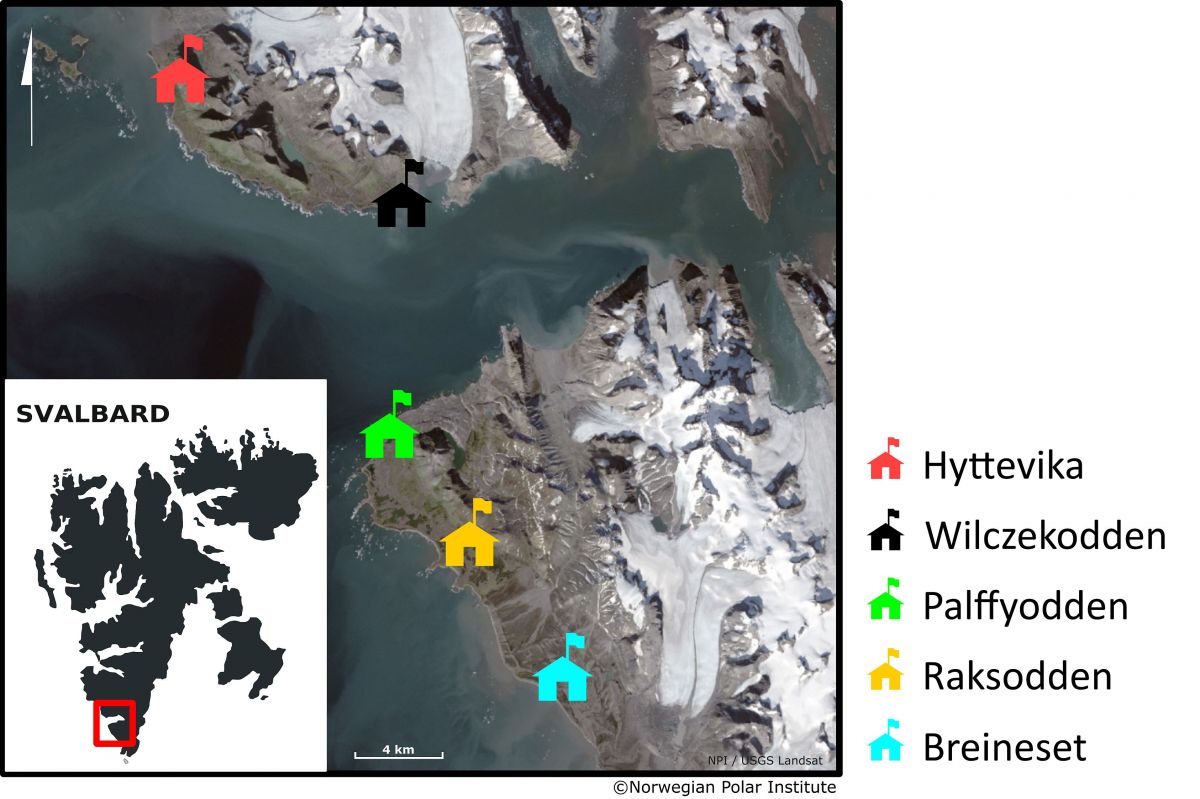

Map by Barbara Jóźwiak

TEXT: Barbara Jóźwiak

SOURCES:

Prestvold, K. (2008) “Svalbard's cultural remains – traces of history in an Arctic landscape”, Norwegian Polar Institute: Cruise Handbook for Svalbard [online]

http://cruise-handbook.npolar.no/en/svalbard/cultural-remains.html

Reymert, P. K., Oddleif, M. (2015) Fangsthytter på Svalbard 1794-2015, Svalbard Museum

Svalbard Environmental Protection Act [online]

https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/svalbard-environmental-protection-act/id173945/

TopoSvalbard, https://toposvalbard.npolar.no/