We have always been interested in what lives and grows around us. This desire to understand the world is one of our most admirable qualities and, at the same time, basic science in its purest form. It was, no doubt, this kind of science that paved the way for the development of civilization.

Since the dawn of time, when early humans made animal paintings on cave walls, through Aristotle and Charles Darwin, until today, curiosity has pushed us to explore the secrets of life. This, in turn, has led to the introduction of the concept of species as the basic unit of classification for living organisms. Providing species with names makes them more familiar and easier to recognize. Examples from outside our windows may include a rabbit hutch spider or a bush cricket called the spiked magician.

If we want to predict the consequences of climate change for the planet’s inhabitants, we must first get to know and define them. The long way we still have ahead of us must lead, among others, to the Arctic, as polar cold is a mere trifle for the bewildering richness of life. The Far North is home to countless species, including one known as the little polar researcher and one named after an inflatable rubber boat.

Why the fuss?

Thanks to biodiversity studies, we know, for example, the numbers and kinds of insects that pollinate plants, the identity of creatures inhabiting ocean depths, and the roles served by microscopic organisms found in front of our houses. We know that the species composition of a given ecosystem can be regarded as a reliable indicator of its functioning and that even subtle composition changes may turn out to be catastrophic. None of this would be known had it not been for the science of defining species, which is to say, taxonomy.

The father of taxonomy is Carl Linnaeus, an 18th-century botanist, whose life goal was to describe and systematize life on Earth. This desire led him to the creation of a uniform binomial nomenclature for naming species. As a result, we are now known as the Homo sapiens, which means that we belong to the genus Homo and our specific name is sapiens, which stands for wise. The fact remains, however, that long before Linnaeus and his nomenclature entered the picture, humans had already dealt with taxonomy, naming and describing species encountered during hunts and in their households.

Taxonomists, whose job is to study the Earth’s biological diversity, not only discover new species, but also find and update old descriptions by adding new data or photographs. Their efforts make it easier to better understand our planet and devise effective environmental protection strategies. Besides, taxonomy is an indispensable tool in the science of systematics, which focuses on the classification of life on Earth. All plants, fungi and animals owe their names to taxonomists. It is therefore no wonder that taxonomy is seen as a sound foundation for the remaining environmental sciences. This, however, has come at a price. The chase for new species cost many scientists their lives, families or sanity.

It will be no exaggeration to say that it was the overwhelming desire to get to the bottom of biodiversity that led to the formulation of the theory of evolution, put forward by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, who was somewhat outshone by his famous colleague. The theory ended up changing the course of the history of science. New species are still being discovered all over the place, even if most of them can only be seen through a microscope. Contrary to general expectation, even cold regions – such as the Arctic – are no terra incognita of new species. Despite harsh conditions, new types of organisms keep turning up in the tundra, lakes and seas.

In terms of biodiversity, one of the best studied regions in the Arctic is the Archipelago of Svalbard. This is due to a network of year-round and seasonal research stations, supporting scientific work, the northernmost university in the world and relatively uncomplicated logistics (Longyearbyen, which is Svalbard’s administrative centre, lies within just a few hours’ flight from Central Europe). There are no new species of bear or reindeer to be found there, but the island crawls with microscopic animals carrying as mysteriously-sounding names as tardigrades, gastrotrichs, kinorhynchs, syringophilidae or eriophyoidea.

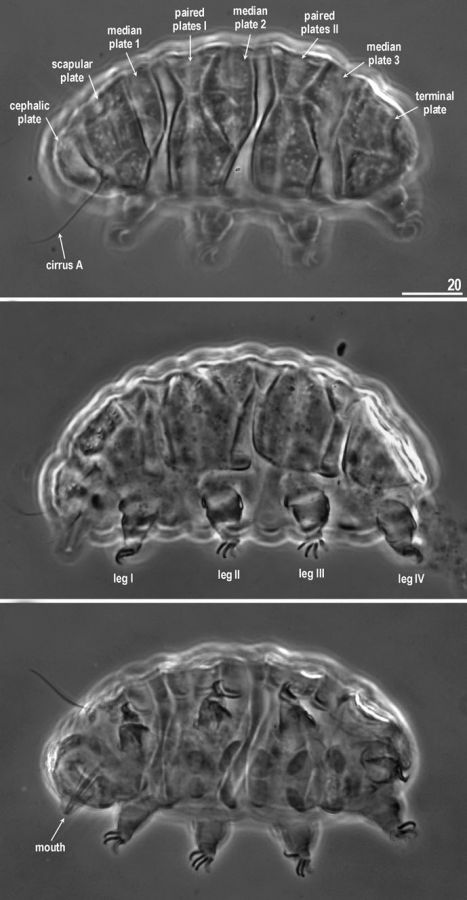

New species of water bears in clumps of moss

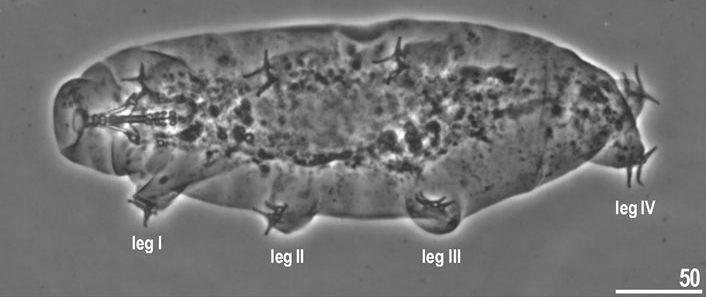

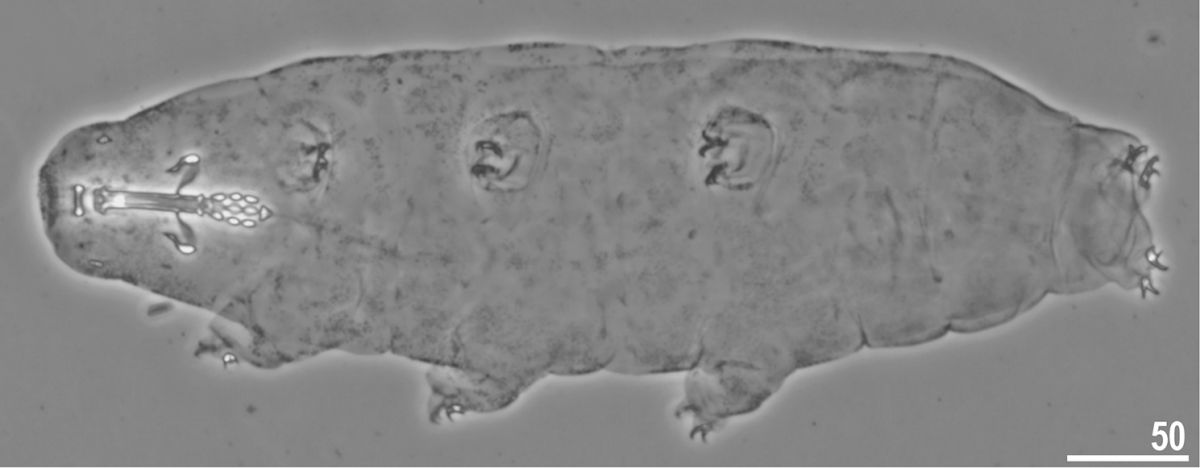

Spitsbergen is not only pointy mountains, vast fiords and giant glaciers, but also lush, low-growing tundra, which can hardly be overlooked by anyone visiting the island’s western coast. Bryophytes and lichens found in Spitsbergen are home to countless tiny animals. The most numerous of them are tardigrades, often referred to as water bears or moss piglets. Tardigrades are seldom larger than 0.3 mm and, observed in a drop of water, they look a lot like clumsy bears with four pairs of limbs. It is this look that got them their nickname.

With the help of scientists from the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, several interesting, new species of Svalbard’s tardigrades have been described within the past decade. Among the species discovered in Revdalen, lying close to the Polish Polar Station Hornsund, was Bryodelphax parvuspolaris, whose specific name denotes a little polar researcher, in honour of polar researchers overwintering at the Station. Discovered on the slope of Rotjesfjellet was a species now known as Isohypsibius coulsoni, after prof. Stephen Coulson, an accomplished polar biologist and ecologist. Right behind the Station, at the foot of Ariekammen, which is a nesting site for a colony of little auks, scientists discovered a species which they named Isohypsibius karenae, in recognition of prof. Katarzyna Wojczulanis-Jakubas, from the University of Gdańsk, who specializes in Arctic birds. Moreover, last year a certain taxonomic puzzle was finally solved. After a thorough analysis of its morphology and genetics, a type of animal which is found in Spitsbergen and which had been known as Mesobiotus obscurus, turned out to be a completely new species. It is now called Mesobiotus occultatus, which means „concealed” (in this case, under a different name). Not only tundra, but also ice hosts new species. Recently on Hansbreen glacier located in the vicinity of Polish Polar Station, a new species have been described, Pilatobius glacialis (means from glacier), Grevenius cryophilus (means cold-loving), and Acutuncus mariae in honor of the mother of the author, Maria Zawierucha.

Little inhabitants of Arctic lakes

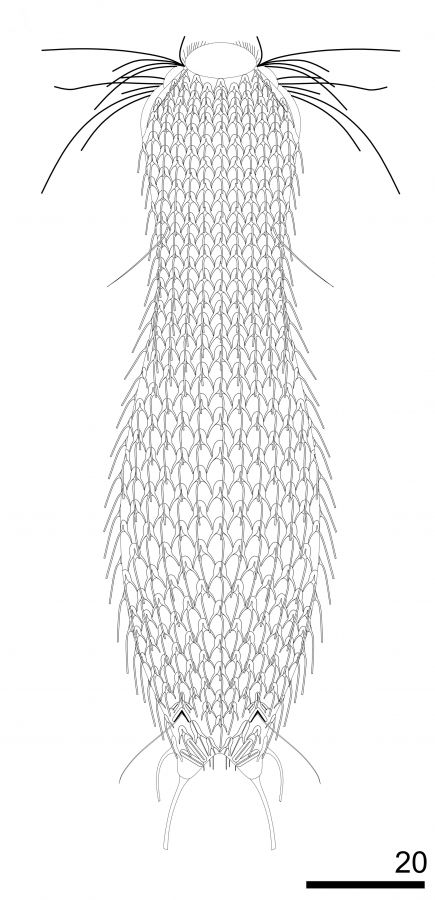

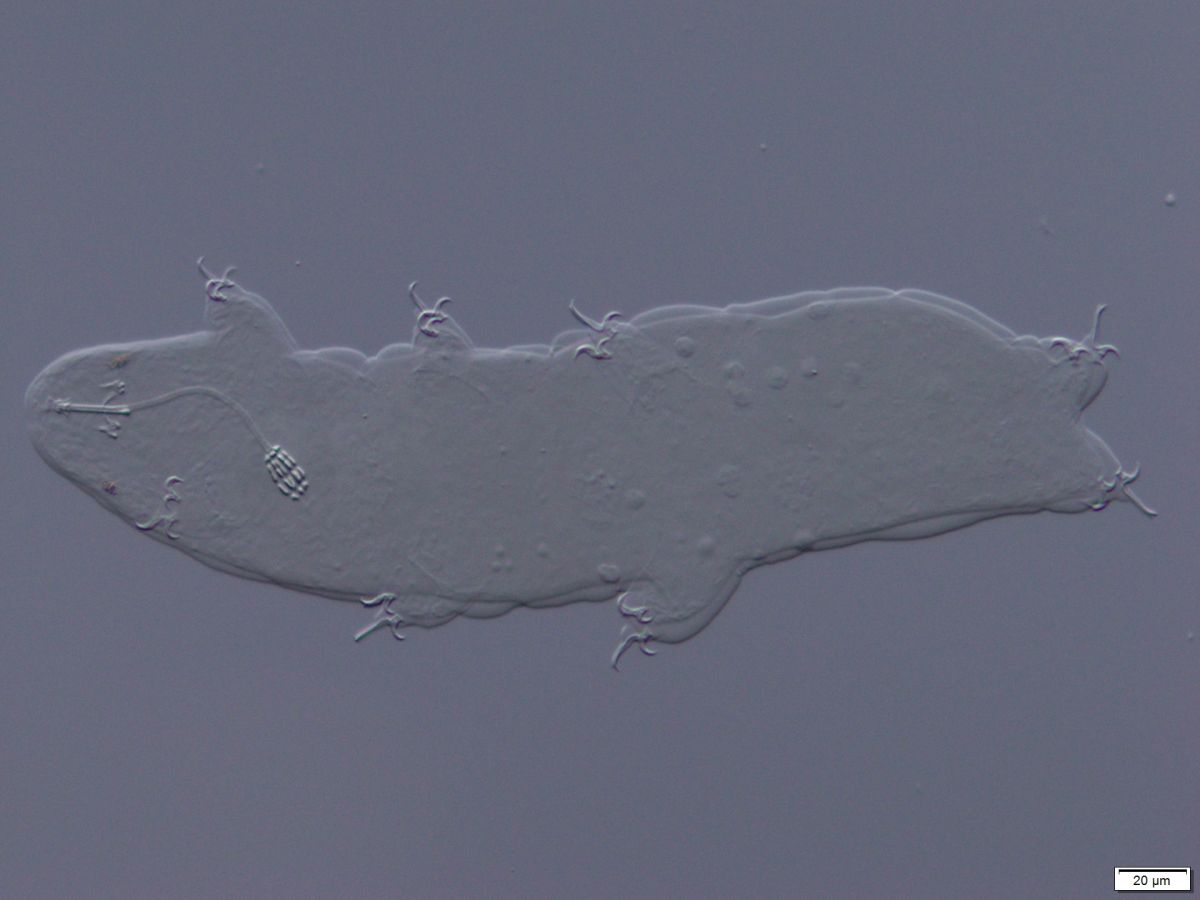

When strolling across Arctic tundra, you are bound to notice little ponds, lakes and streams. Sediments found at their bottom are populated by enigmatic marine animals known as gastrotrichs or, more colloquially, hairybellies. Despite their wide geographical distribution (from the tropics to polar regions) and substantial numbers in water bodies, hairybellies are one of the least studied animal groups on the planet. Their flat, bottle-shaped bodies fork at one end and tend to measure about 0.1 mm. Found on their bellies are rows of cilia (to which hairybellies owe their nickname), while their backs are covered with an astonishing variety of scales, hooks and spines.

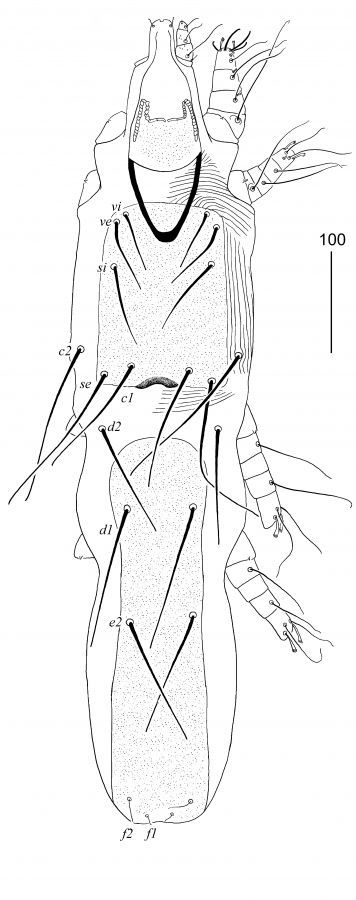

Unfortunately, there is only a handful of scientists in the world who specialize in gastrotrichs, among them Małgorzata Kolicka, PhD, who spares no effort to describe new species discovered in Spitsbergen. It is thanks to her that we have recently been introduced to a few more types of Arctic gastrotrichs. Among them was Chaetonotus (Chaetonotus) bombardus, named after a Bombard inflatable boat, which was used to transport microscopes needed for analyses. The name of Chaetonotus (Chaetonotus) subtilis, on the other hand, was inspired by subtle scales covering its body. Finally, Chaetonotus (Hystricochaetonotus) hornsundi was named after a place all readers of EDU-ARCTIC.PL are already familiar with, namely the Hornsund fiord, where the species had been discovered.

Undiscovered arthropods

If you’re lucky enough to spend any length of time in Spitsbergen, you will surely come across birds. One of the largest species readily encountered on the tundra is the barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis). Its feathers, which are a common sight around the edges of ponds, lakes and streams, are often inhabited by parasitic mites by the name of syringophilidae. These enigmatic arthropods live inside feather quills (or the hollow shafts we usually hold feathers by) and look like they’ve come from another planet. In fact, they do have their own mobile planets in the form of flying birds! A feather picked up near Nisenfjella in Spitsbergen turned out to contain a representative of a whole new type of syringophilidae, which came to be known as Chenophila nanseni. Its specific name was inspired by the famous Norwegian explorer, scientist and diplomat – Fridtjof Nansen.

On your way back towards the ship, keep an eye out for plants by the name of saxifrages, which may be found on rocks and fine gravel. It was in this type of plant that scientists discovered a new species of eriophyoidea. Just like syringophilidae, the animals are parasitic mites, but they prefer plants to bird feathers. Their parasitic activity disfigures the plants by causing unsightly growths (cecidia). This, according to some, is only natural, as the eriophyoidea themselves are not exactly pretty. Rather than dwelling on the animals’ physical beauty (or lack thereof), let us instead consider them from the point of view of natural selection. They have only two (instead of four) pairs of limbs and elongated bodies, which make them clearly stand out among their mite cousins. A species discovered in Hornsund Fiord – Cecidophyes siedleckii – was named in honour of Stanisław Siedlecki, an accomplished geologists and one of the founders of the Polish Polar Station Hornsund.

Sea dragons

Sooner or later, you will have to get back on board the ship and leave the Arctic shore. While standing on the beach and watching the rippling surface of the fiord, you may not realize that the sand under your feet and the bottom of the fiord are inhabited by the kinorhyncha, often referred to as mud dragons – microscopic creatures which may easily compete with hairybellies for the title of the least studied animal.

They resemble segmented pencils, with tips lined with rows of hooks. To add piquancy to the description, we should mention they’re carnivores, which means they truly are sea monsters, even if rather tiny (usually no more than 1 mm in length). As was the case with hairybellies, scientists who specialize in mud dragon are few and far between. One of them is dr Katarzyna Grzelak from the Institute of Oceanology PAS in Sopot. Recently, with the help of her Danish colleagues, she described mud dragon species from the waters of Svalbard, whose newly acquired names are bound to resonate with fantasy enthusiasts. They include, among others, Cristaphyes dordaidelosensis, whose name was inspired by Dor Daidelos – the region of everlasting cold from J. J. R. Tolkien’s “The Silmarillion”, and Cristaphyes scatha, named after one of the dragons featuring in the same novel. Echinoderes daenerysae, on the other hand, was named in honour of Daenerys Targaryen, the Mother of Dragons from the novels by George R.R. Martin.

There is of course a lot more to say about biodiversity studies and curious names of species discovered in Spitsbergen, especially that recent years have seen a number of new plant and animal species being described (and named). We must remember, however, that in the Arctic true biodiversity starts where the naked eye fails. In other words, the above-mentioned animals do not even come close to exhausting the subject, as they share their habitat with various types of crustaceans, roundworms, rotifers, springtails, enchytraeidae and plenty more tiny Arctic beauties.

Author: Krzysztof Zawierucha, PhD

Fig. 1. Tardigrade Bryodelphax parvuspolaris (photo: Ł. Kaczmarek, K. Zawierucha et al.)

Fig. 2. Tardigrade Isohypsibius coulsoni (photo: Ł. Kaczmarek, K. Zawierucha et al.)

Fig. 3. Tardigrade Isohypsibius karenae (photo: K. Zawierucha)

Fig. 4. Tardigrade Mesobiotus occultatus (photo: Ł. Kaczmarek, K. Zawierucha, M. Gawlak, M. Roszkowska)

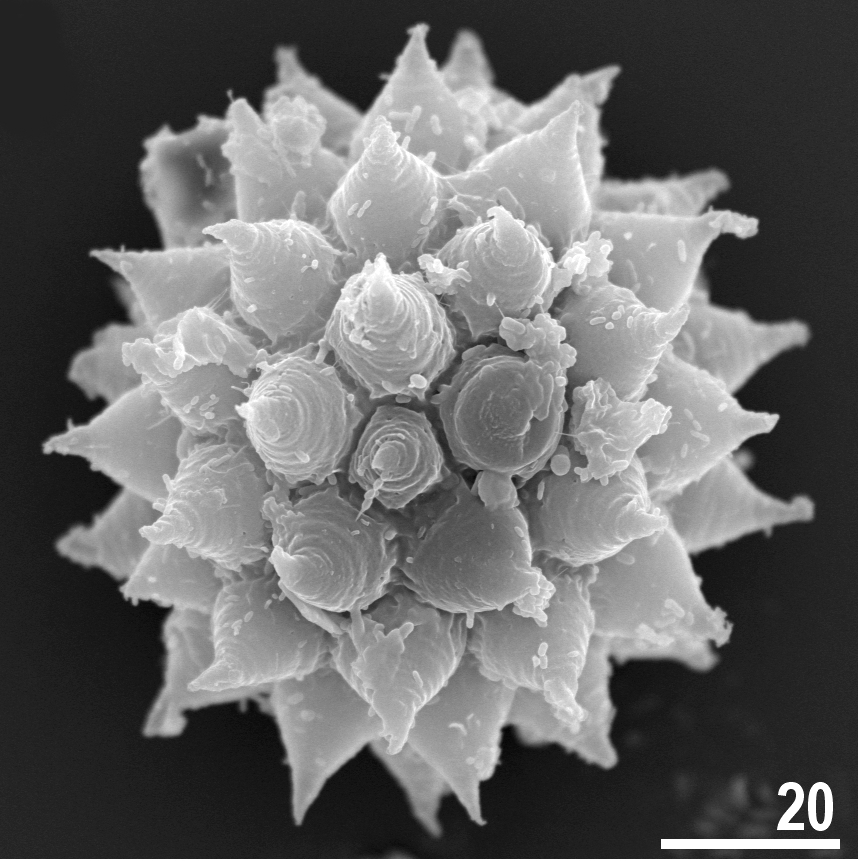

Fig. 5. Egg of tardigrade Mesobiotus occultatus (photo: Ł. Kaczmarek, M. Gawlak, M. Roszkowska)

Fig. 6. Drawing of gastrotrich Chaetonotus (Chaetonotus) bombardus (M. Kolicka)

Fig. 7. Drawing of syringophilidae Chenophila nanseni (M. Skoracki)

Fig. 8. Eriophyoidea Cecidophyes siedleckii (photo: A. Kiedrowicz, W. Szydło, A. Skoracka)

Fig. 9. Kinorhyncha Echinoderes daenerysae (photo: K. Grzelak)

Fig. 10. Tardigrade Pilatobius glacialis (photo: K. Zawierucha)

Bibliography:

Dimante-Deimantovica, I., Walseng, B., Chertoprud, E.S., Novichkova, A. 2018. New and previously known species of Copepoda and Cladocera (Crustacea) from Svalbard, Norway – who are they and where do they come from? Fauna norvegica 38: 18–29.

Grzelak, K., Sørensen, M. 2018. New species of Echinoderes (Kinorhyncha: Cyclorhagida) from Spitsbergen, with additional information about known Arctic species. Marine Biology Research 14: 113-147

Kaczmarek, Ł., Zawierucha, K., Buda, J., Stec, D., Gawlak, M., Michalczyk, Ł., Roszkowska, M. 2018. An integrative redescription of the nominal taxon for the Mesobiotus harmsworthi group (Tardigrada: Macrobiotidae) leads to descriptions of two new Mesobiotus species from Arctic. PLoS ONE, 13(10): e0204756.

Kolicka, M., Kotwicki, L., Dabert, M. 2018. Diversity of Gastrotricha on Spitsbergen (Svalbard archipelago, Arctic) with a description of seven new species. Annales zoologici 68(4): 609-739.

Kiedrowicz, A., Rector, B.G., Zawierucha, K., Szydło, W., Skoracka, A. 2016. Phytophagous mites (Acari: Eriophyoidea) recorded from Svalbard, including the description of a new species. Polar Biology 39: 1359-1368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-015-1858-x

Skoracki, M., Zawierucha, K. 2016. Chenophila nanseni sp. n. (Acari: Syringophilidae) parasitising the barnacle goose in Svalbard. Polish Polar Research 37: 121-130.

Sørensen, M., Grzelak, K. 2018. New mud dragons from Svalbard: three new species of Cristaphyes and the first

Arctic species of Pycnophyes (Kinorhyncha: Allomalorhagida: Pycnophyidae). PeerJ 6:e5653; DOI 10.7717/peerj.5653

Zawierucha, K. 2013. Tardigrada from Arctic tundra (Spitsbergen) with description of Isohypsibius karenae sp. n. (Isohypsibiidae). Polish Polar Research 34(4): 383-396.