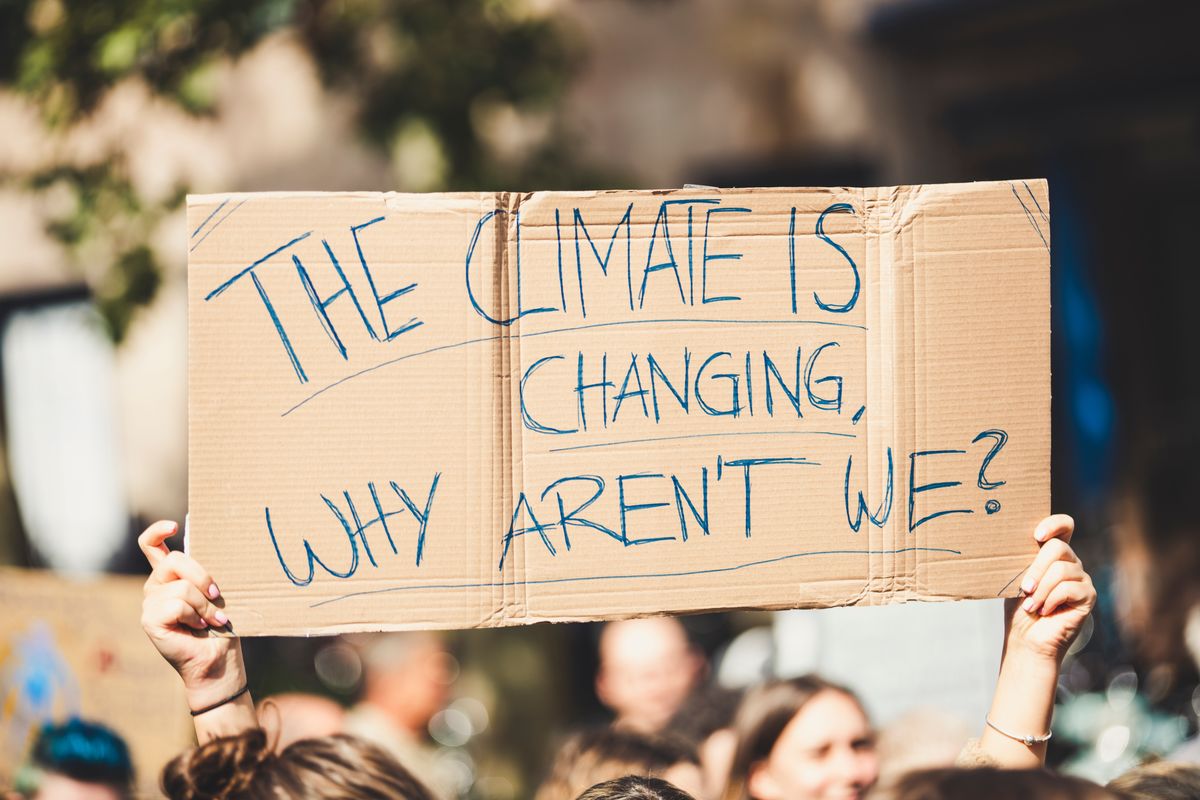

When did people turn their backs on science? What has led to widespread scepticism and a growing tendency to challenge the methods of scientific inquiry? Who is to blame for the situation? The public, who find conspiracy theories more satisfying than scientific facts? Or the scientists, who – focused on ever more complex data, models and charts – have failed to convince the society that we’re all part of the growing civilisation of knowledge? Or is it, perhaps, that scepticism towards science actually stimulates progress? After all, the Greek word “skeptikos” meant someone “inquiring” and “reflective”, who might have well been dissatisfied, but spared no effort to find the truth.

Even though deep scepticism has long been a typical response to new scientific theories (those of Copernicus, Descartes or Kepler were all initially dismissed as heresies), its intensity has become much greater in the 21st century. Despite the increasing reliability of data, widespread consensus among scientists and overwhelming evidence, scientific discoveries are met with a growing pseudo-scientific distrust. Everything is seen as questionable, with the topic of climate change and the intense emotion it provokes being perhaps the most glaring example.

“But wait a second”, you may say. “Isn’t challenging popular beliefs, thinking outside the box and asking difficult questions a vital prerequisite for progress? After all, that’s the approach adopted by Copernicus, Darwin and many others, whose discoveries shaped our perception of the world”. Of course! But the majority of climate-change sceptics follow a very different approach, undermining the fundamental principles of science, disregarding the laws of nature, and ignoring valid scientific evidence that contradicts their ideas. It is true that, at first glance, some arguments put forward by climate-change sceptics seem logical, convincing and grounded in hard science, but appearances are deceptive. While their arguments are not downright lies, they are invariably based on incomplete information and are therefore seriously misleading.

Here are six of the most common myths and scientifically-sound responses that debunk them:

MYTH 1: “Global warming? But it was terribly cold yesterday!”

This misconception is both the most common and the easiest to understand, as it doesn’t take much to lose sight of the difference between current weather phenomena and long-term climate trends. An unpleasantly cold summer day in your hometown has nothing to do with a long-term increase in global temperature. In order to notice climate trends it is necessary to observe changes in the weather over a longer period of time. What appeals to our imagination, however, are record temperatures, and high temperature records occur twice as often as low temperature ones. What makes the myth even more confusing is that one of the reasons behind extremely cold winters in the northern hemisphere is the loss of sea ice in the Arctic, which is to say, global warming. In a nutshell, the melting of sea ice in the far north affects the temperature and salinity of ocean water, which – in turn – upsets the functioning of the global system of sea currents, which have so far been responsible for the mild climate in coastal areas. Another important factor is the so-called polar vortex and the fact that the reduction in the amount of sea ice causes changes in atmospheric pressure. It is these changes that were responsible for the winter Armageddon that hit New York, leaving the locals to deal with empty shelves in supermarkets and frozen hydrants.

MYTH 2: “The climate has changed before, so there’s nothing to worry about.”

The climate has indeed changed during Earth’s history and has included both colder and warmer periods. The fact remains, however, that sudden increases in temperature on a global scale have generally been catastrophic for life on the planet, causing mass extinctions, like the so-called Great Dying at the end of the Permian. Climate changes associated with these events include a considerable and rapid increase in global temperatures, a rise in sea level and growing acidity of ocean water, which are the exact same phenomena we’re dealing with today. What is more, the global warmings of the past were always related to a relatively high content of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere. And although it is true that life flourished in the Eocene, the Cretaceous and other periods when the CO2 content in the atmosphere was rather high, this was possible because greenhouse gasses were in a state of balance with carbon contained in ocean water and the process of weathering occurring on land. Atmospheric gases, chemistry of the oceans and living creatures had millions of years to adjust to these levels. Sudden changes, on the other hand, have invariably had a devastating impact on life.

MYTH 3: „Alright, so things are changing, but it’s not our fault. It’s the Sun that determines what our climate is like.”

In this case, a reply is rather short. Fine, the Sun is our main source of energy and its activity does fluctuate periodically (with a period of about 11 years). The thing is, though, that for the last 40 years the Sun has been considerably less active and the temperatures keep going up nonetheless. If the amount of solar energy is reduced and the Earth continues to get warmer, the Sun can’t be the main factor behind the Earth’s temperature. Simple as that.

MYTH 4: “It’s not carbon dioxide that the problem. We should worry about water vapour instead.”

Contrary to what many people think, the gas that’s chiefly responsible for the greenhouse effect is indeed water vapour. Climate-change sceptics, however, use the fact to suggest that the increasing concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is no cause for concern, which – once again – exposes their selective approach to facts. An issue they choose to ignore this time is that the climate is a system. The amount of water vapour in the atmosphere depends on the temperature, as the higher the temperature the more water evaporates, turning into water vapour. If, therefore, a different gas causes the temperature to rise (as is the case, for example, with extra CO2 produced when burning fossil fuels), the rate of evaporation rises too. Additional water vapour causes a further increase in temperature, creating a vicious circle or the so-called positive feedback loop. In other words, climate-change sceptics are right to suggest that, in terms of its amount in the atmosphere, water vapour is a dominant greenhouse gas. What they fail to mention is that the positive feedback loop associated with water vapour makes temperature changes caused by CO2 twice as great as they would normally be.

MYTH 5: “Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities are very small compared to the amount of CO2 emitted naturally.”

They truly are tiny, but don’t let this mislead you. A lethal dose of potassium cyanide is tiny too. Moreover, natural CO2 is not static. It is generated as a result of natural processes and absorbed by the ecosystem. Although our output of 29 gigatons of CO2 may seem negligible compared to the 750 gigatons moving through the carbon cycle each year, nature can only absorb about 40% of the surplus. The rest of it gradually accumulates in the atmosphere.

As for the popular claim that volcanos emit more carbon dioxide than humans, it is simply not true. Anthropogenic CO2 emissions are a hundred times higher than volcanic emissions.

MYTH 6: “Climate changes aren’t all that bad.”

Wouldn’t it be great to have orange groves outside Warsaw or the sunny paradise of the Maldives in Kołobrzeg? A list of potential advantages of global warming is as long as it is exciting and includes, among others, intensive plant growth (also in the far north), agricultural expansion, and new opportunities for development, exploitation of natural resources and transport in a world free of sea ice. Unfortunately, the risks far outweigh any potential benefits. Among them are catastrophic weather phenomena, massive waves of migration, devastated cities, limited access to drinking water, floods, droughts, and rampant diseases. If you think such prospects are as far-removed from your daily life as sinking islands in the Pacific, think again. Whether we like it or not, Europe will not become a beneficiary of climate changes and Poland will not turn into a tropical paradise. Global warming will have a range of unpleasant consequences, from a destabilized economy, erratic energy supply or even total blackouts, through severe droughts causing catastrophic crop failures and food shortages, to forest fires and lethal heat waves. Apart from dying coral reefs that we so often hear about, global warming is a serious risk for infrastructure and invaluable architectural heritage, with tremendous amounts of money necessary to adapt to climate changes and alleviate their consequences. It’s the tragedy of Venetians standing helpless in the face of destructive floods and of those who fell victim to tornadoes that swept through Polish forests. The Earth will surely survive, but it will no longer be the place that made our civilisation possible to develop.

And now, just for a brief moment, let’s assume that climate-change sceptics are right. Climate changes aren’t certain, they may be unrelated to human activity, and their consequences may be nothing to lose sleep over. Let’s ignore measurements, models and the shared opinion of 99% of all world’s scientists, who are sure the opposite is the case. Climate is an immensely complex system. Our observations are incomplete and our models may not be 100% accurate. We do not understand all mechanisms behind climate change. Can we, however, afford to ignore what we do understand?

Author: Anna Wielgopolna

Translation: Barbara Jóźwiak